The processes are analyzed from different perspectives within different contexts, notably in the fields of linguistics, anesthesia, neuroscience, psychiatry, psychology, education, philosophy, anthropology, biology, systemics, logic, and computer science.

These and other different approaches to the analysis of cognition are synthesised in the developing field of cognitive science, a progressively autonomous academic discipline. Within psychology and philosophy, the concept of cognition is closely related to abstract concepts such as mind and intelligence. It encompasses the mental functions, mental processes (thoughts), and states of intelligent entities (humans, collaborative groups, human organizations, highly autonomous machines, and artificial intelligences).

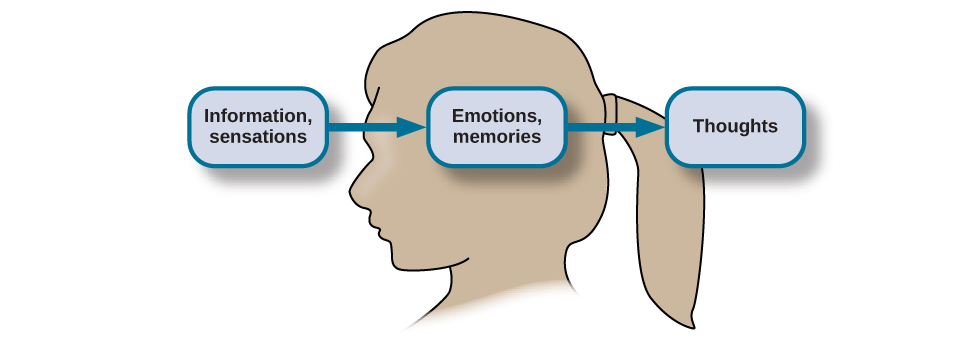

Thus, the term's usage varies across disciplines; for example, in psychology and cognitive science, "cognition" usually refers to an information processing view of an individual's psychological functions. It is also used in a branch of social psychology called social cognition to explain attitudes, attribution, and group dynamics. In cognitive psychology and cognitive engineering, cognition is typically assumed to be information processing in a participant’s or operator’s mind or brain. Cognition can in some specific and abstract sense also be artificial.

Cognition is a word that dates back to the 15th century, when it meant "thinking and awareness". Attention to the cognitive process came about more than eighteen centuries ago, beginning with Aristotle and his interest in the inner workings of the mind and how they affect the human experience. Aristotle focused on cognitive areas pertaining to memory, perception, and mental imagery. The Greek philosopher found great importance in ensuring that his studies were based on empirical evidence; scientific information that is gathered through observation and conscientious experimentation. Centuries later, as psychology became a burgeoning field of study in Europe and then gained a following in America, other scientists like Wilhelm Wundt, Herman Ebbinghaus, Mary Whiton Calkins, and William James, to name a few, would offer their contributions to the study of cognition.

Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) heavily emphasized the notion of what he called introspection: examining the inner feelings of an individual. With introspection, the subject had to be careful to describe his or her feelings in the most objective manner possible in order for Wundt to find the information scientific. Though Wundt's contributions are by no means minimal, modern psychologists find his methods to be quite subjective and choose to rely on more objective procedures of experimentation to make conclusions about the human cognitive process.

Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850–1909) conducted cognitive studies that mainly examined the function and capacity of human memory. Ebbinghaus developed his own experiment in which he constructed over 2,000 syllables made out of nonexistent words, for instance EAS. He then examined his own personal ability to learn these non-words. He purposely chose non-words as opposed to real words to control for the influence of pre-existing experience on what the words might symbolize, thus enabling easier recollection of them. Ebbinghaus observed and hypothesized a number of variables that may have affected his ability to learn and recall the non-words he created. One of the reasons, he concluded, was the amount of time between the presentation of the list of stimuli and the recitation or recall of same. Ebbinghaus was the first to record and plot a "learning curve," and a "forgetting curve." His work heavily influenced the study of serial position and its effect on memory, discussed in subsequent sections.

Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was an influential American pioneer in the realm of psychology. Her work also focused on the human memory capacity. A common theory, called the recency effect, can be attributed to the studies that she conducted. The recency effect, also discussed in the subsequent experiment section, is the tendency for individuals to be able to accurately recollect the final items presented in a sequence of stimuli. Her theory is closely related to the aforementioned study and conclusion of the memory experiments conducted by Hermann Ebbinghaus.

William James (1842–1910) is another pivotal figure in the history of cognitive science. James was quite discontent with Wundt's emphasis on introspection and Ebbinghaus' use of nonsense stimuli. He instead chose to focus on the human learning experience in everyday life and its importance to the study of cognition. James' major contribution was his textbook Principles of Psychology that preliminarily examines many aspects of cognition like perception, memory, reasoning, and attention, to name a few.